|

Havell Name

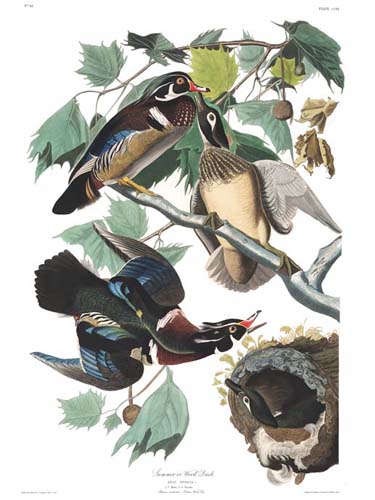

Summer or Wood Duck Common Name Wood Duck Havell Plate No. 206 Paper Size 39" x 28" Image Size 35" x 24" Price $ 1,200 |

||||

|

Ornithological Biography I have always experienced a peculiar pleasure while endeavouring to study the habits of this most beautiful bird in its favourite places of resort. Never on such occasions have I been without numberless companions, who, although most of them were insensible of my presence, have afforded me hours of the never-failing delight resulting from the contemplation of their character. Methinks I am now seated by the trunk of a gigantic sycamore, whose bleached branches stretch up towards the heavens, as if with a desire to overlook the dense woods spread all around. A dark-watered bayou winds tortuously beneath the maples that margin its muddy shores, a deep thicket of canes spreading along its side. The mysterious silence is scarcely broken by the hum of myriads of insects. The blood-sucking musquito essays to alight on my hand, and I willingly allow him to draw his fill, that I may observe how dexterously lie pierces my skin with his delicate proboscis, and pumps the red fluid into his body, which is quickly filled, when with difficulty he extends his tiny wings and flies off, never to return. Over the withered leaves many a tick is seen scrambling, as if anxious to elude the searching eye of that beautiful lizard. A squirrel spread flat against a tree, with its head directed downwards, is watching me; the warblers too, are peeping from among the twigs. On the water, the large bull-frogs are endeavouring to obtain a peep of the sun; suddenly there emerges the head of an otter, with a fish in its jaws, and in an instant my faithful dog plunges after him, but is speedily recalled. At this moment, when my heart is filled with delight, the rustling of wings comes sweeping through the woods, and anon there shoots overhead a flock of Wood Ducks. Once, twice, three times, have they rapidly swept over the stream, and now, having failed to discover any object of alarm, they all alight on its bosom, and sound a note of invitation to others yet distant.

Scenes like these I have enjoyed a thousand times, yet regret that I have not enjoyed them oftener, and made better use of the opportunities which I have had of examining the many interesting objects that attracted my notice. And now, let me endeavour to describe the habits of the Wood Duck, in so far as I have been able to apprehend them. This beautiful species ranges over the whole extent of the United States, and I have seen it in all parts from Louisiana to the confines of Maine, and from the vicinity of our Atlantic coasts as far inland as my travels have extended. It also occurs sparingly during the breeding-season in Nova Scotia; but farther north I did not observe it. Everywhere in this immense tract I have found it an almost constant resident, for some spend the winter even in Massachusetts, and far up the warm spring waters of brooks on the Missouri. It confines itself, however, entirely to fresh water, preferring at all times the secluded retreats of the ponds, bayous, or creeks, that occur so profusely in our woods. Well acquainted with man, they carefully avoid him, unless now and then during the breeding-season, when, if a convenient spot is found by them in which to deposit their eggs and raise their young, they will even locate themselves about the miller’s dam. The flight of this species is remarkable for its speed, and the ease and elegance with which it is performed.The Wood Duck passes through the woods and even amongst the branches of trees, with as much facility as the Passenger Pigeon; and while removing from some secluded haunt to its breeding-grounds, at the approach of night, it shoots over the trees like a meteor, scarcely emitting any sound from its wings. In the lower parts of Louisiana and Kentucky, where they abound, these regular excursions are performed by flocks of from thirty to fifty or more individuals. In Several instances I have taken perhaps undue advantage of their movements to shoot them on the wing, by placing myself between their two different spots of resort, and keeping myself concealed. In this manner I have obtained a number in the course of an hour of twilight; and I have known some keen sportsmen kill as many as thirty or forty in a single evening. This sport is best in the latter part of autumn, after the old males have joined the flocks of young led by the females. Several gunners may then obtain equal success by placing themselves at regular distances in the line of flight, when the birds having in a manner to run the gauntlet, more than half of a flock have been brought down in the course of their transit. While passing through the air on such occasions, the birds are never heard to emit a single note. The Wood Duck breeds in the Middle States about the beginning of April, in Massachusetts a month later, and in Nova Scotia or on our northern lakes, seldom before the first days of June. In Louisiana and Kentucky, where I have had better opportunities of studying their habits in this respect, they generally pair about the 1st of March, sometimes a fortnight earlier. I never knew one of these birds to form a nest on the ground, or on the branches of a tree. They appear at all times to prefer the hollow broken portion of some large branch, the hole of our large Woodpecker (Picus principalis), or the deserted retreat of the fox-squirrel; and I have frequently been surprised to see them go in and out of a hole of any one of these, when their bodies while on wing seemed to be nearly half as large again as the aperture within which they had deposited their eggs. Once only I found a nest (with ten eggs) in the fissure of a rock on the Kentucky river a few miles below Frankfort. Generally, however, the holes to which they betake themselves are either over deep swamps, above cane-brakes, or on broken branches of high sycamores, seldom more than forty or fifty feet from the water. They are much attached to their breeding-places, and for three successive years I found a pair near Henderson, in Kentucky, with eggs in the beginning of April, in the abandoned nest of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker. The eggs, which are from six to fifteen, according to the age of the bird, are placed on dry plants, feathers, and a scanty portion of down, which I believe is mostly plucked from the breast of the female. They are perfectly smooth, nearly elliptical, of a light colour, between buff and pale green, two inches in length by one and a half in diameter; the shell is about equal in firmness to that of the Mallard’s egg, and quite smooth. No sooner has the female completed her set of eggs than she is abandoned by her mate, who now joins others, which form themselves into considerable flocks, and thus remain apart until the young are able to fly, when old and young of both sexes come together, and so remain until the commencement of the next breeding season. In all the nests which I have examined, I have been rather surprised to find a quantity of feathers belonging to birds of other species, even those of the domestic fowl, and particularly of the Wild Goose and Wild Turkey. On coming upon a nest with eggs when the bird was absent in search of food, I have always found the eggs covered over with feathers and down, although quite out of sight, in the depth of a Woodpecker’s or Squirrel’s hole. On the contrary, when the nest was placed in the broken branch of a tree, it could easily be observed from the ground, on account of the feathers, dead sticks, and withered rrasses about it. If the nest is placed immediately over the water, the young, the moment they are hatched, scramble to the month of the hole, launch into the air with their little wings and feet spread out, and drop into their favourite element; but whenever their birth-place is at some distance from it, the mother carries them to it one by one in her bill, holding them so as not to injure their yet tender frame. On several occasions, however, when the hole was thirty, forty, or more yards from a bayou or other piece of watery I observed that the mother suffered the young to fall on the grasses and dried leaves beneath the tree, and afterwards led them directly to the nearest edge of the next pool or creek. At this early age, the young answer to their parents’ call with a mellow pee, pee, pee, often and rapidly repeated. The call of the mother at such times is low, soft, and prolonged, resembling the syllables pee-ee, pee-ee. The watch-note of the male, which resembles hooked, is never uttered by the female; indeed, the male himself seldom uses it unless alarmed by some uncommon sound or the sight of a distant enemy, or when intent on calling passing birds of his own species. The young are carefully led along the shallow and grassy shores, and taught to obtain their food, which at this early period consists of small aquatic insects, flies, musquitoes, and seeds. As they grow up, you now and then see the whole flock run as it were along the surface of the sluggish stream in chase of a dragon-fly, or to pick up a grasshopper or locust that has accidentally dropped upon it. They are excellent divers, and when frightened instantly disappear, disperse below the surface, and make for the nearest shore, on attaining which they run for the woods, squat in any convenient place, and thus elude pursuit. I used two modes of procuring them alive on such occasions. One was with a bag net, such as is employed in catching our little Partridge, and which I placed half sunk in the water, driving the birds slowly, first within the wings, and finally into the bag. In this manner I have caught young and old birds of this species in considerable numbers. The other method I accidentally discovered while on a shooting excursion, accompanied by an excellent pointer dog. I observed that the sight of this faithful animal always immediately frightened the young Ducks to the shores, the old one taking to her wings as soon as she conceived her brood to be safe. But the next instant Juno would dash across the bayou or pond, reach the opposite bank, and immediately follow on their track. In a few moments she would return with a duckling held between her lips, when I would take it from her unhurt. While residing at Henderson, I thought of taming a number of Wood Ducks. In the course of a few days Juno procured for me, in the manner above described, as many as I had a mind for, and they were conveyed home in a bag. A dozen or more were placed in empty flour barrels, and covered over for some hours, with the view of taming them the sooner. Several of these barrels were placed in the yard, but whenever I went and raised their lids, I found all the little ones hooked by their sharp claws to the very edge of their prisons, and, the instant that room was granted, they would tumble over and run off in all directions. I afterwards frequently saw these young birds rise from the bottom to the brim of a cask, by moving a few inches at a time up the side, and fixing foot after foot by means of their diminutive hooked claws, which, in passing over my hand, I found to have points almost as fine as those of a needle. They fed freely on corn-meal soaked in water, and as they grew, collected flies with great expertness. When they were half-grown I gave them great numbers of our common locusts yet unable to fly, which were gathered by boys from the trunks of trees and the, “iron weeds,” a species of wild hemp very abundant in that portion of the country. These I would throw to them on the water of the artificial pond which I had in my garden, when the eagerness with which they would scramble and fight for them always afforded me great amusement. They grew up apace, when I pinioned them all, and they subsequently bred in my grounds in boxes which I had placed conveniently over the water, with a board or sticks leading to them, and an abundant supply of proper materials for a nest placed in them. Few birds are more interesting to observe during the love-season than Wood Ducks. The great beauty and neatness of their apparel, and the grace of their motions, always afford pleasure to the observer; and, as I have had abundant opportunities of studying their habits at that period, I am enabled to present you with a full account of their proceedings. When March has again returned, and the Dogwood expands its pure blossoms in the sun, the Cranes soar away on their broad wings, bidding our country adieu for a season, flocks of water-fowl are pursuing their early migrations, the frogs issue from their muddy beds to pipe a few notes of languid joy, the Swallow has just arrived, and the Blue-bird has returned to his box. The Wood Duck almost alone remains on the pool, as if to afford us an opportunity of studying the habits of its tribe. Here they are, a whole flock of beautiful birds, the males chasing their rivals, the females coquetting with their chosen beaux. Observe that fine drake! how gracefully he raises his head and curves his neck! As he bows before the object of his love, he raises for a moment his silken crest. His throat is swelled, and from it there issues a guttural sound, which to his beloved is as sweet as the song of the Wood Thrush to its gentle mate. The female, as if not unwilling to manifest the desire to please ;which she really feels, swims close by his side, now and then caresses him by touching his feathers with her bill, and shews displeasure towards any other of her sex that may come near. Soon the happy pair separate from the rest, repeat every now and then their caresses, and at length, having sealed the conjugal compact, fly off to the woods to search for a large Woodpecker’s hole. Occasionally the males fight with each other, but their combats are not of long duration, nor is the field ever stained with blood, the loss of a few feathers or a sharp tug of the head being generally enough to decide the contest. Although the Wood Ducks always form their nests in the hollow of a tree, their caresses are performed exclusively on the water, to which they resort for the purpose, even when their loves have been first proved far above the ground on a branch of some tall sycamore. While the female is depositing her eggs, the male is seen to fly swiftly past the hole in which she is hidden, erecting his crest, and sending forth his love-notes, to which she never fails to respond. On the ground the Wood Duck runs nimbly and with more grace than most other birds of its tribe. On reaching the shore of a pond or stream, it immediately shakes its tail sidewise, looks around, and proceeds in search of food. It moves on the larger branches of trees with the same apparent ease; and, while looking at thirty or forty of these birds perched on a single sycamore on the bank of a secluded bayou, I have conceived the sight as pleasing as any that I have ever enjoyed. They always reminded me of the Muscovy Duck, of which they look as if a highly finished and flattering miniature. They frequently prefer walking on an inclined log or the fallen trunk of a tree, one end of which lies in the water, while the other rests on the steep bank, to betaking themselves to flight at the sight of an approaching enemy. In this manner I have seen a whole flock walk from the water into the woods, as a steamer was approaching them in the eddies of the Ohio or Mississippi. They swim and dive well, when wounded and closely pursued, often stopping at the edge of the water with nothing above it but the bill, but at other times running to a considerable distance into the woods, or hiding in a cane-brake beside a log. In such places I have often found them, having been led to their place of concealment by my dog. When frightened, they rise by a single spring from the water, and are as apt to make directly for the woods as to follow the stream. When they discover an enemy while under the covert of shrubs or other plants on a pond, instead of taking to wing, they swim off in silence among the thickest weeds, so as generally to elude your search, by landing and running over a narrow piece of ground to another pond. In autumn, a whole covey may often be seen standing or sitting on a floating log, pluming and cleaning themselves for hours. On such occasions the knowing sportsman commits great havoc among them, killing half a dozen or more at a shot. The food of the Wood Duck, or as it is called in the Western and Southern States, the Summer Duck, consists of acorns, beech-nuts, grapes, and berries of various sorts, for which they half-dive, in the manner of the Mallard for example, or search under the trees on the shores and in the woods, turning over the fallen leaves with dexterity. In the Carolinas, they resort under night to the rice-fields, as soon as the grain becomes milky. They also devour insects, snails, tadpoles, and small water lizards, swallowing at the same time a quantity of sand or gravel to aid the trituration of their food. The best season in which to procure these birds for the table is from the beginning of September until the first frost, their flesh being then tender, juicy, and in my opinion excellent. They are easily caught in figure-of-four traps. I know a person now residing in South Carolina, who has caught several hundreds in the course of a week, bringing them home in bags across his horse’s saddle, and afterwards feeding them in coops on Indian corn. In that State, they are bought in the markets for thirty or forty cents the pair. At Boston, where I found them rather abundant during winter, they bring Dearly double that price; but in Ohio or Kentucky twenty-five cents are considered an equivalent. Their feathers are as good as those of any other species; and I feel well assured that, with a few years of care, the Wood Duck might be perfectly domesticated, when it could not fail to be as valuable as it is beautiful. Their sense of hearing is exceedingly acute, and by means of it they often save themselves from their wily enemies the mink, the polecat, and the racoon. The vile snake that creeps into their nest and destroys their eggs, is their most pernicious enemy on land. The young, when on the water, have to guard against the snapping-turtle, the gar-fish, and the eel, and in the Southern Districts, against the lashing tail and the tremendous jaws of the alligator. Those which breed in Maine, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, move southward as soon as the frosts commence, and none are known to spend the winter so far north. I have been much surprised to find WILSON speaking of the Wood Ducks as a species of which more than five or six individuals are seldom seen together. A would-be naturalist in America, who has had better opportunities of knowing its habits than the admired author of the “American Ornithology,” repeats the same error, and, I am told, believes that all his statements are considered true. For my own part, I assure you, I have seen hundreds in a single flock, and have known fifteen to be killed by a single shot. They, however, raise only one brood in the season, unless their eggs or young have been destroyed. Should this happen, the female soon finds means of recalling her mate from the flock which he has joined. On having recourse to a journal written by me at Henderson nearly twenty years ago, I find it stated that the attachment of a male to a female lasts only during one breeding season; and that the males provide themselves with mates in succession, the strongest taking the first choice, and the weakest being content with what remains. The young birds which I raised, never failed to make directly for the Ohio, whenever they escaped from the grounds, although they never had been there before. The only other circumstances which I have to mention are, that when entering the hole in which its nest is, the bird dives as it were into it at once, and does not alight first against the tree; that I have never witnessed an instance of its taking possession, by force, of a Woodpecker’s hole; and lastly, that during winter they allow Ducks of different species to associate with them. Dr. BACHMAN, who has kept a male of this species several years, states that after moulting he is for six weeks of a plain colour, like the young males, and the feathers gradually assume their bright tints. The tree represented in the plate is the Platanus occidentalis, which in different parts of the United States is known by the names of Buttonwood, Sycamore, Plane-tree, and Water Beech, and in Canada by that of Cotton-tree. It is one of our largest trees, and on the banks of our great western and southern rivers often attains a diameter of eight or ten feet. Although naturally inclined to prefer the vicinity of water, it grows in almost every kind of situation, and thrives even in the streets of several of our eastern cities, such as Philadelphia and New York. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

| Home | Gallery | Audubon Biography | About Edition | Testimonials | Authorized Dealers | Links | Contact Us |

© Copyright 2007-2025 Zebra Publishing, LLC. | All Rights Reserved Terms of Use

Powered by Fusedog Media Group